Yves here. Even though this article frames trust around trust in politicians, one could argue that broader societal trust may be at least as relevant. As readers know well, the US has become a highly unequal society in a comparatively short period of time. Unequal societies are low trust societies. Neolibearlism separately reduces trust by encouraging individuals to view themselves as atomized, both as consumers and as workers, and the resulting low attachment to companies and communities also diminishes trust. We’ve also had a increase in paranoid parenting, with children having to be picked up from school and escorted to play dates, when crime rates are way lower than in the era of “free range” children.

By Olivier Bargain, Professor of Economics, University of Bordeaux and Ulugbek Aminjonov, PhD Candidate, Bordeaux University. Originally published at VoxEU

As a second wave of COVID-19 threatens the health of communities across the globe, governments are considering another round of lockdowns. But the success of those policies will depend largely on the levels of compliance, which will in turn depend on the confidence that citizens have in their leaders. This column summarises the results of recent studies examining the effect of civic trust during the first wave of the pandemic. The evidence points to a higher rate of compliance with stay-at-home policies in regions with a higher level of long-term trust in politicians.

As many countries are facing the second wave of COVID-19, governments are still wondering how to best contain the diffusion of the virus (Chudik et al 2020). Beyond the fact that new lockdowns would simply cost too much to the economy, shelter-in-place policies seem increasingly unacceptable to citizens, especially those who show distrust towards authorities and question the ability of leaders to manage the crisis (Daniele et al. 2020). Trust is a fundamental factor analysed in economics, for instance for its influence on tax compliance. Last year, social movements in France and Chile reminded us that degraded trust in institutions can harm social cohesion and economic stability. At present, a spreading distrust in the face of a massive pandemic may have dramatic consequences when compliance is required for collective survival (Painter and Qiu 2020).

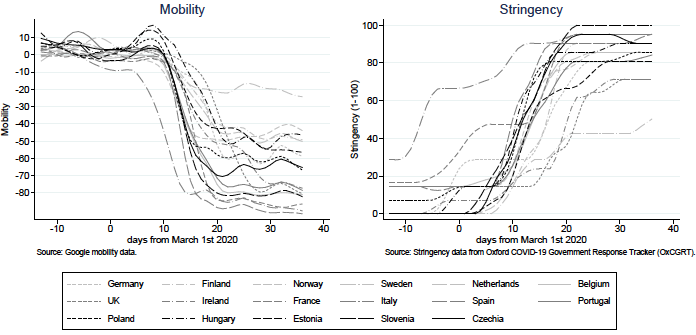

The importance of trust in government, social capital, and political beliefs as drivers of compliance have been analysed since the onset of the COVID crisis, as nicely reviewed by Giuliano and Rasul (2020). In a recent paper, we discuss the effect of long-term levels of trust in politicians on human mobility during March and April 2020 (Bargain and Aminjonov 2020). The human mobility index is obtained from Chan et al. (2020) and constructed based on the Google COVID-19 mobility reports. Using information on the number of visits to (or length of stay at) different locations, mobility is recorded and compared to a baseline period of 3 January to 6 February. In the left panel of Figure 1, we illustrate mobility trends across European countries (we use here the index for locations under the “retail and recreation” category, but similar patterns are observed with other types of locations). The sharp decline in mobility around mid-March reflects the compliance with national shelter-in-place policies. The timing and cross-country variation also coincide with the intensity of the social distancing policies enacted during this period, as measured by a policy stringency index and shown in the right panel of Figure 1. This index, provided by the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT) and described in Hale et al. (2020), combines information on the extent of restrictions imposed by local governments to tackle the rapid outbreak of COVID-19.

Figure 1 Daily mobility and lockdown stringency in Europe around March 2020

We focus on the correlation between trust and mobility at the regional level in Europe, exploiting trust variation within and across countries. Trust measures, taken from the European Social Survey (ESS), reflect citizens’ answers about their trust in politicians on a scale from zero (“no trust at all”) to ten (“complete trust”). Trust is recorded prior to the COVID crisis, consistent with our intention to discard trust that is context-dependent, and focus on long-term variation in civic trust across regions, as forged by historical, political, and social developments of the past (Tabellini 2010).

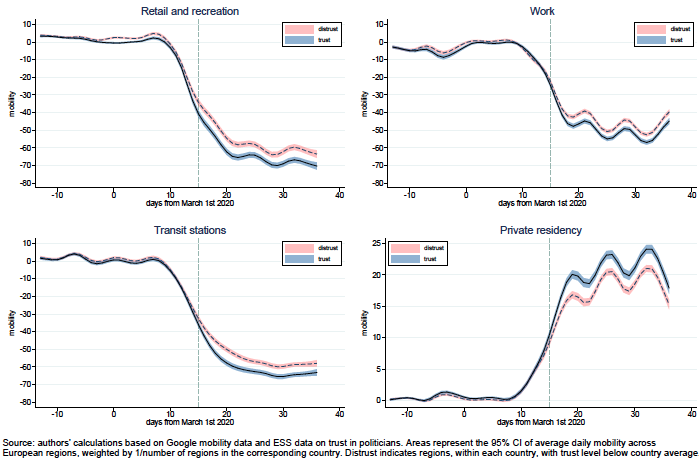

We show that the drop in human mobility is stronger – indicating a higher degree of compliance with containment rules – where the regional level of trust in politicians is high. This is illustrated in Figure 2, splitting regions into two groups: regions with an average trust score above (“trust”) or below (“distrust”) the national average. For each group, areas represent the 95% confidence intervals of average daily mobility across European regions. The four graphs show results for different types of non-necessary mobility (time spent at recreational places, at work, or in transport) or, inversely, for time spent at home.

Econometric estimations confirm the main result. We use a difference-in-difference approach, i.e. comparing low and high trust regions before and after lockdown enactments, while controlling for region fixed effects.1 The effect appears fairly large: high-trust regions have decreased their mobility by around 15% more than low-trust regions. It is also suggestive to see that this pattern mainly concerns non-necessary activities (we find no effect in trust regarding the mobility to grocery stores or pharmacies). Finally, results are confirmed when using alternative measures of appreciation for the political system, including the ESS question on satisfaction with the work of the national government, and the question on trust in the national government from the Eurobarometer.

Figure 2 Daily mobility and trust in politicians: variation across European regions

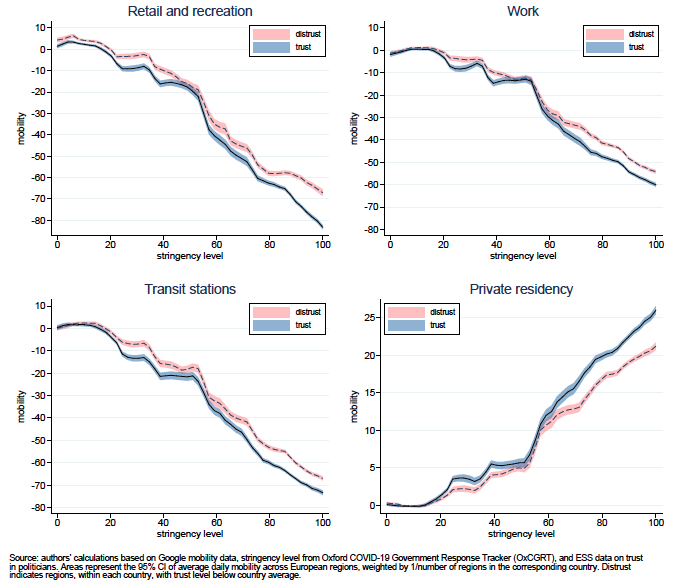

We also use the daily intensity of policy stringency as a more continuous source of variation in treatment, over time and across countries. Most European countries have gradually enacted measures of varying severity, from generalised lockdowns to a milder mitigation approach (for instance, in the UK initially, and in Sweden throughout the period). Exploiting regional variation again, Figure 3 illustrates the negative relationship between mobility for non-essential activities and policy stringency (or the positive relation between stringency and time spent at home). In other words, stricter lockdown policies have been more effective in reducing human movements, which is crucial to limiting contagion. We also see that at a given stringency level, higher trust leads to a further reduction in mobility, hence a better compliance with shelter-in-place directives. That is, trust increases the efficiency of these measures, and all the more so as stringency was high (the gap between trust and distrust regions increases with the stringency level). Econometric estimations confirm the mediating effect of trust on the efficacy of policy stringency in terms of mobility reduction.

Figure 3 Daily mobility, lockdown stringency and political trust in March and April 2020

To establish the link between trust and COVID-19 casualties through its effect on mobility, we calculate an elasticity of daily upcoming death growth rate with respect to mobility.2 Combined with the estimated relationship between trust and mobility, we find that a standard deviation increase in trust in Europe is associated with a 6.5% decrease in the growth rate of COVID-19 fatalities. To put things in perspective, recall that the death toll was around 2,000 by mid-March and 90,000 by mid-April in Europe overall.3 The compounded effect of trust indicates that a standard-deviation higher level of trust in Europe would have led to approximately 10,000 fewer casualties by mid-April.

Thus, public health policies are significantly more effective if they receive public support and are implemented in a context of social cohesion. Regional differences in attitudes towards policymakers is a key ingredient for governments to consider when designing nationwide policies. Other studies confirm these findings for other parts of the world. In particular, Brodeur et al. (2020) proceed as we do with trust data and Google mobility reports, exploiting regional variation in the US. They find that stay-at-home orders reduce mobility more in high-trust counties. Similar results are found in studies using different notions of civic values. Barrios et al. (2020) focus on electoral participation to proxy civic capital, while Engle et al. (2020) show more response to local restriction orders in counties that did not support Republicans during the last presidential elections. Another paper examines mobility variation in Europe using only broad country variation and proxying civic values by voter turnout at European elections (Bartscher et al. 2020). Other papers use disaggregated variation within specific countries, such as recent evidence on the ‘willingness to distance’ in Denmark (Olsen and Hjorth 2020), or variation in civic capital in Italy, a resource also shown to mediate the social distancing process (Durante et al. 2020).

In times of national emergencies, the attempt by politicians to regain trust is vital. This can be done through different channels, including a much clearer communication about what we know from scientists, more pedagogy to explain the reasons underlying public action, and intertemporal consistency in political decisions. As put forward by Giuliano and Rasul (2020), the most important aspect may be the ability of governments to persuade people to internalise the externality they would impose on the community by not reducing their mobility or asking them to wear masks. Enlighted leaders should acknowledge that limiting freedom is hard, but that this is the principle of civil liberty, which is always better than the natural freedom (Hobbes) that leads to violence. After all, a state that cares about my ability to stay healthy tends to enhance my freedom to accomplish things in life in the longer run. Governments should also show more trust themselves by agreeing to decentralise responsibilities to locally elected politicians, such as mayors. This ‘reverse’ trust is cruelly lacking in very centralised states such as France. It is striking to see that it is in the countries which are already federalised that further decentralisation is promoted – as in a recent policy shift in Germany that delegates more responsibility to the county level – and in particular for the management of the crisis.

See original post for references