Yves here. Many of you in the US likely missed the A level testing algo fiasco. Here is the short version, from the Financial Times yesterday:

The government is under mounting pressure to come to the aid of secondary school pupils in England after almost 40 per cent of A-level grades were downgraded from teachers’ predictions.

Amid an angry backlash from pupils and teachers, opposition parties and trade unions led calls for ministers to review how A-level results were modified by examination regulators using a computer algorithm.

But Boris Johnson, prime minister, defended the contentious arrangements aimed at preventing unwarranted grade inflation, saying there had been a “robust” marking system.

With exams cancelled because of the coronavirus crisis, A-level results released on Thursday were calculated through a two-part process: teachers estimated pupils’ grades, and then Ofqual, the watchdog, moderated the qualifications through statistical modelling that factored in schools’ past performance, among other considerations.

And a related Financial Times story alludes to the fact, as has no doubt occurred to many US parents, how Covid-19 is further reducing already low class mobility. Only a small subset of kids are motivated enough to take online study to heart; the most affluent can hire tutors; some but not very many parents have the breadth of knowledge, time, and temperament to home school.

Sarah Akintunde admits to being “scared”. The 18-year-old from Romford in Essex hopes to study law at Oxford university from September but needs Thursday’s A-level results to deliver top grades to do so.

If that prospect was already daunting, the disruption of coronavirus and the scrapping of exams this year, in favour of a series of statistical assessments, means that the future for the 700,000 A-level students due to get their results in England, Wales and Northern Ireland this week is even more uncertain than normal….

The stakes are particularly high for students from ethnic minorities, like Ms Akintunde, those from low-income backgrounds and from other groups traditionally under-represented in higher education — including white working class boys, Roma and mature students.

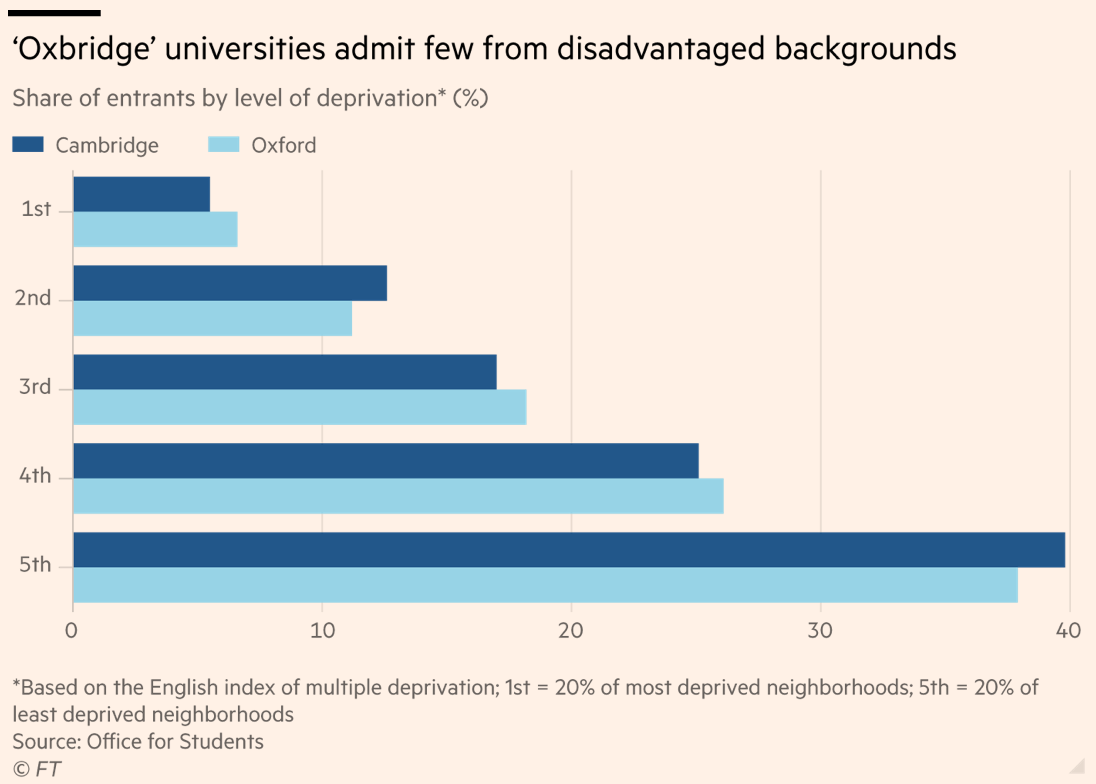

The barriers that students from these backgrounds face remain formidable. Data from the Office for Students, the university regulator, show that those admitted to Oxford and Cambridge are around 15 times less likely to come from the UK’s poorest districts than its richest ones. Across more than 25 of the more prestigious universities from Birmingham to York, young people from the richest areas of the country are on average four times more likely to attend than those from the poorest…

Even before coronavirus — and despite more than £550m being spent annually on boosting access — progress had been slow. The share of students from the least wealthy fifth of British districts attending higher education has risen from 11.6 per cent to 12 per cent in the past five years; and for black students from 5.8 per cent to 6.6 per cent. Universities such as Oxford had announced bold plans this year to expand their intake of students from low-income backgrounds.

Now, there is concern that coronavirus threatens to reverse even the small progress that has been made. The fear, among teachers and specialists is that less privileged school leavers will receive lower grades given that the marking algorithms deployed to substitute for written exams are based partly on a school’s past record rather than the individual’s potential.

Richard Murphy worries that Covid-19 interrupted public education won’t go away any time soon, and authorities and gatekeepers aren’t prepared.

By Richard Murphy, a chartered accountant and a political economist. He has been described by the Guardian newspaper as an “anti-poverty campaigner and tax expert”. He is Professor of Practice in International Political Economy at City University, London and Director of Tax Research UK. He is a non-executive director of Cambridge Econometrics. He is a member of the Progressive Economy Forum. Originally published at Tax Research UK

make no apology for returning to the A level theme that I have noted for a couple of days. This blog is a stream of consciousness, as much as anything. It represents my reaction to world events, and in my world this has been a big deal for the last few days. My son and I are, we now know, amongst the lucky ones. We could celebrate last night, and not all could.

This year’s results are not, however, my main concern this morning. Next year’s are. And they are just as important to those who will be taking them as this years have been to people like my son. The prospect that those results will be severely impacted by the coronavirus crisis is very real. And that is an issue I have not seen anyone mention in the mainstream media as yet.

There is an assumption that this year’s results will be aberrational: a disruption in an otherwise smooth flow of results that would otherwise exist from 2019 to 2021, but that is not true. In fact, it is likely to be very far from it. I can, in fact, make a fairly confident set of predictions right now, presuming that there are A level exams in 2021, and nothing should be taken for granted at present.

The first is that students from private schools will perform at way above average level. Their schooling has been relatively uninterrupted during the summer term of 2020, largely because it was reasonable for those schools to presume that every pupil could partake in online learning.

Second, and inversely, state school performance will be worse. They could not deliver a continuing curriculum during a crucial term, or provide the exam training that is, rightly or wrongly, a key part of that team’s work for their pupils. Those pupils will not be as well prepared as is desirable as a result. That is the consequence of their inability to assume all pupils could access online learning.

And third, the impact noted in my second point will be exaggerated by income factors. The lower a pupil’s parental income is likely to be the harder access to education during the last term was also likely to be, through lack of IT resource, uninterrupted space to study, and so on.

As a result it is entirely possible to say now, and with absolute certainty, that next year’s A level results will not see a return to normal.

It is equally certain that those results will be heavily biased in favour of those pupils with the best off parents, and most especially those who have attended private schools.

It follows that without allowing for this fact the 2021 A level results will fail next year’s sixth formers, and most especially those from lower income households attending state schools. That means planning to correct for this has to start now, unless the government is indifferent to the injustice this will give rise to.

And nor will the problem end there. Those aged 15 who will be taking GCSEs next year are also impacted by this. The consequences will flow through to their post 16 choices and A levels. There is very likely impact in that case until the 2023 A level results, at least.

My question in that case is a simple one, and is what is to be done about this, unless we are to be indifferent to the resulting prejudice? This year’s mess can be dismissed as a fiasco, even if an utterly arbitrarily unfair one. But next year’s issue is wholly anticipatable, because I am doing that now. It cannot be avoided in that case. And I suggest that the injustice cannot be avoided either.

So what is to be done? I have no answers, at least as yet. I do not claim that I can formulate answers to every problem I can foresee arising. But unless this issue is addressed now the scale of the anger at the injustices that will result will be even greater than this year, where some degree of forgiveness for the mess is at least possible on the part of some. Next year there will be no such tolerance.

The key issue is that we are not going back to normal.

And that means that ministers need to prepare for that reality.

And so, too, does everyone else.

The post-Covid world is not going to be the same as the pre-Covid one. We need to embrace that reality. Few have. And ministers do not appear to be amongst those few. It’s time they rose to the challenge, and prepared the ground. How society develops from here depends upon them doing so.