In July, shortly after Turkish society emerged from COVID lockdown, members of the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) proposed withdrawing the country from the Istanbul Convention. Signed by Turkey in 2011, the Convention creates a European legal framework for preventing, prosecuting and eliminating violence against women and domestic violence. Arguments that the convention ‘weakens the institution of the family’ and ‘encourages homosexuality’ were consistent with the culture of anti-feminism and patriarchalism long encouraged by the AKP. However, in the context of a recent wave of femicides, the prospect of losing one of the few legal protections for vulnerable has women provoked outrage, reaching all the way into the conservative camp. What follows is the English translation of a comment published in the September issue of Turkish journal Varlık by the poet and philosopher Betül Dünder, together with an open letter signed by 155 female writers and poets, entitled ‘No to violence, yes to the Istanbul Convention’. Eurozine.

During the first three months of the pandemic, people withdrew from the streets, public squares, halls, and stadiums into their homes. Humankind saw and experienced domestic living from a variety of angles and in multifarious shapes and forms. People were forced to remove themselves from nature, which they had formerly paid no mind to, fanning the flames of the great fire consuming it on a daily basis. During the pandemic, they returned to their own human nature. Forced to stay inside their homes, which had formerly served them as a shelter, a safe harbour from the madding crowd, people tried to abide by ‘the principles of survival’. At least, they did until the re-opening of streets in June, which marked the beginning of a new phase known as ‘normalization’. After that, it was back to square one.

We know the story from beginning to end. Social relations in the public realm have long become a site of threat under the reign of dominant manhood. The transformation of women and LGBTIQ+ individuals into a community of ‘others’ dancing with death is the most visible form of segregation and hostility against those who are unlike or not associated with oneself. The current government’s resistance to all proposals to eliminate gender inequality, its dismissal of the unjust treatment of children and women, and its creation of new authorities on the basis of these inequalities are issues we are already familiar with. From where we stand, the story of this endless conflict and struggle is the very stuff of history. Because we know from experience – both personal and inherited – what it means to be the ‘second sex’ that makes those headlines. Those narratives, storing our experiences of womanhood, come together to make an album of resistance.

Manhood – and the sanctity attributed to it – cannot exist without the women who obey, who comply, who belong exclusively to him, who meet his every need, emotional and physical. In a domain where patriarchy merges with feudalism, those who resist have no chance of survival. We have witnessed how those deaths classified in the past as ‘honour killings’ were partially removed from ‘our’ reality, how they were interpreted through a lens of feudalism ascribed to ‘the East’ of the country. We are familiar with the idea that this ‘primitive violence’ was the destiny of those lands, with racially biased arguments that it is none other than women who perpetuate the practice of this moral law.

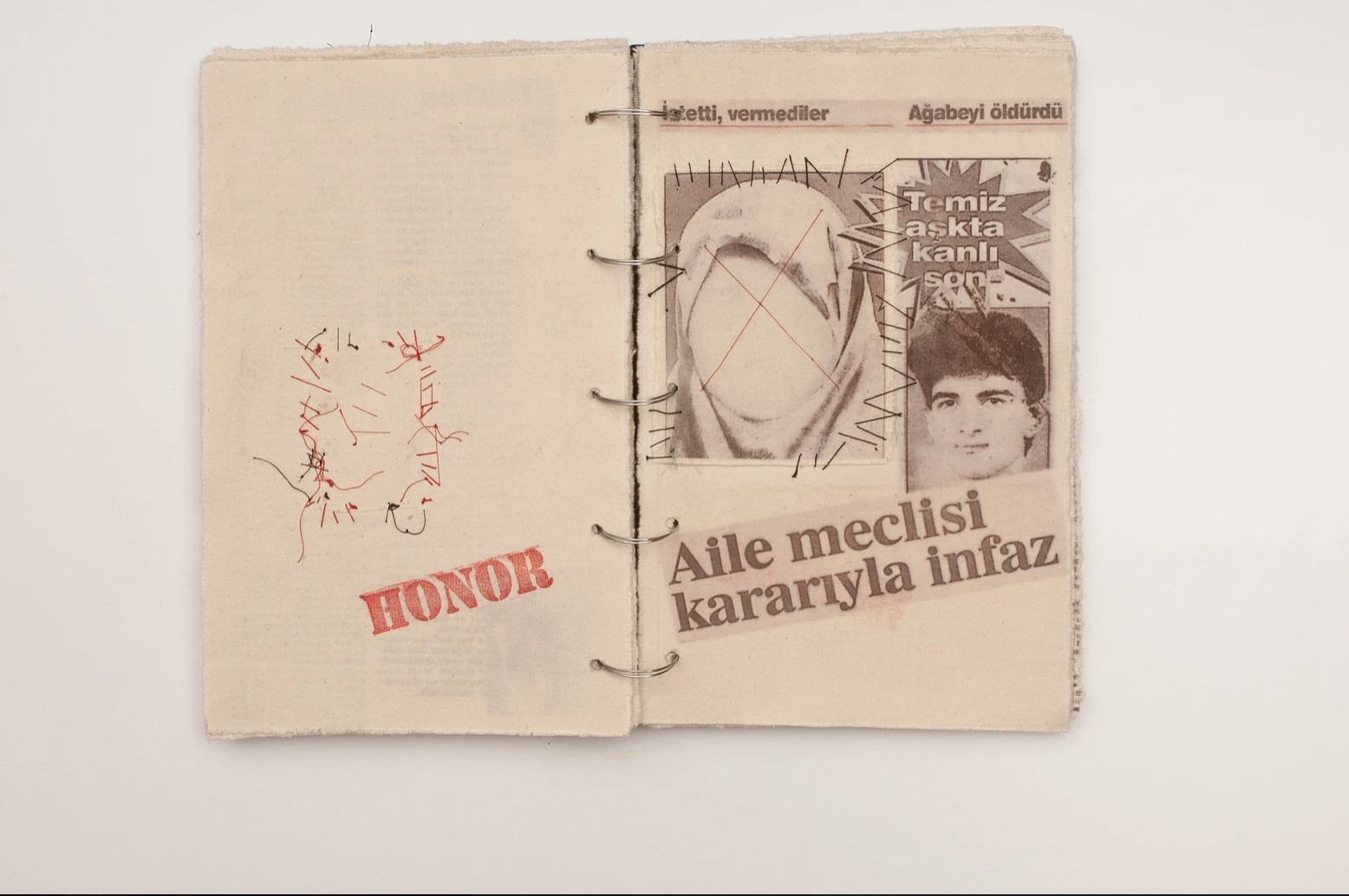

NAMUS/HONOR is a book by artist Ipek Duben of honour killings and domestic violence in Turkey and other countries in the world. It begins in 1998 and continues to the present. Is it ever going to end? Credit: Ipek Duben

But the headlines changed long ago. We are no longer talking about honour killings, for they are now known as ‘femicides’. From the north of the country to the south, from the west coast to the east and through to the inner territories, we receive news of women being brutally murdered. Merely stating that all these lives, which beg for sociological analysis and debate, are by no means isolated cases, and that these femicides are in fact political in nature, makes us stand out in the eyes of the government. Those women who stand shoulder to shoulder, crying ‘not male justice, real justice’, going after the perpetrators, holding them accountable for each life lost; they cannot be sure that it’s not going to be their names tomorrow on the posters or on social media, or called out by their sisters spilling out into the streets in anger and protest.

Because the circle tightens. It is only a matter of time for a woman sharing on her social media page a defiant outcry about a murder to be the subject of the next outcry. In order to prevent these murders from becoming just a postscript, in order to break this chain of violence and, most importantly, to create a network that will help each and every woman from all strata of society to survive this abuse, this violence, these rapes and murders, building solidarity between women is an absolute sine qua non. Because those are our names going up on the wall of The Monument Counter. Because the Monument Counter is a ballad of dead women!

The full name is ‘The Council of Europe Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence Against Women and Domestic Violence’. ‘The Istanbul Convention’ is the short name used by the women who campaign against a government that recently proposed withdrawing its ratification. Opened for signature on 11 May 2011 in Istanbul, the Convention ‘opens the path for creating a legal framework at pan-European level to protect women against all forms of violence, and prevent, prosecute and eliminate violence against women and domestic violence’. Would it be too far-fetched to say that, since law 6284 implementing the Convention came into force, negligence regarding gender equality and all forms of discrimination has led us to become a country of murderers?

As a result of the resistance put up by feminists and LGBTIQ+ individuals, who used the power of social media and exposed societal hypocrisy in the face of the vulgar rhetoric generated by the government and quickly adopted by the grassroots (‘prostitution will escalate, homosexuality will rise’), and of their efforts to convince people that the Istanbul Convention is a human rights treaty that supports life, not death and violence, the convention has been embraced by large sections of society. Possibly the most unexpected example was the declaration by KADEM (Women and Democracy Association), which has an organic connection with the government, and which now opposed the withdrawal of ratification.

During the entire process, what impressed me most was the open letter written by a number of authors/poets right before the ‘Great Women’s Protest’ held across the nation on 5 August 2020, calling the government to take responsible action to implement the conditions of the convention (see below). The text, entitled ‘No to violence, yes to the Istanbul Convention’, was signed by 155 women writers. It was quickly disseminated by the national press and did a lot to shape public opinion. Numerous female literary figures who somehow could not be reached at the time of signing published posts in various social media – especially Twitter – declared their support for the convention with the hashtag #bendevarım (‘count me in’). That the text was the product of a collective effort and there was a race against time for its publication before the protest is meaningful in itself.

Ever since the ‘Declaration of Sentiments’ of 1847, composed by the American suffragette Elizabeth Cady Stanton on ‘women’s status and rights in social, civil and religious spheres’ and often said to be the world’s first declaration of women’s rights, we have known what we are capable of in the fight against all discrimination and violence. We have lived, written and co-existed in full awareness of our responsibility. In response to those who stand in opposition to the Istanbul Convention, we would like to quote a verse by the poet Gülten Akın: ‘Humanity is responsibility’.

We are bearing witness to the rapid transformation of the language used in our society into a discriminatory form that aggravates violence and marginalizes groups of people. With incidents of abuse, rape and murder increasing on a daily basis, the ideal of a non-violent society, a fundamental need of humankind, is being destroyed. It is impossible for us to keep silent in the face of this! Despite Turkey being a signatory country of the Istanbul Convention, the implementational flaws and deficiencies over the last nine years have caused incidents of femicide escalate into an epidemic.

As the debate around the convention continues, the number of bricks representing the murdered women on the Monument Counter is multiplying and the wall of death continues to rise. Those who murder women and abuse children believe that they will not receive any retribution for their deeds. Benefiting from the absence of social and legal consequences, they continue to abuse, rape and murder. Their appetite for destruction is insatiable.

The convention was signed in 2011 to ensure that gender equality becomes a standard life practice in society. When the expectation is for the convention to be implemented under all conditions, debating our withdrawal from it is simply unacceptable! We cannot live, create or be ourselves under the assault of dominant manhood and masculinity! For the state to demonstrate that it cares about its citizens and that it will rise in defense of all people’s right to life, regardless of gender and sexuality, the Istanbul Convention serves as a pledge. The Convention is about taking a pro-life stand.

We, the women who try to exist as writers, bearing the honorable weight of Gülten Akın’s verse “Have I misunderstood, humanits is responsibility”, invite those with authority and responsibility to become a party to the Istanbul Convention, in order to ensure its swift implementation.