Austrian Romani Holocaust Survivor Ceija Stojka painted this rendering of what happened in the showers of Auschwitz. Photo via The Advocacy Project from Flickr.

On 9 July, 2020, the European Parliament held a plenary debate titled, ‘Boosting Roma inclusion process in Europe for the next decade’ where Italian MEP Annalisa Tardino made the following statement:

‘Roma have set up criminal networks, avoid census, while we are all registered. They exploit their own children, force them to beg, and they are denied the right to go to school. The state must intervene here. It must abolish the degradation that is characteristic of the lives of Roma people in our cities, which endanger public order and health.’[1]

French MEP France Jamet echoed this sentiment by adding,

‘How can I explain to my compatriot that… we decide to spend more money, time, and resources to integrate a population that doesn’t want to be [integrated]. Faced with adversity and in light of the current crisis, we must choose to defend France and the French people first.’[2]

The language of these European parliamentary representatives come far too close to the decree issued 84 years earlier on June 6, 1936 by a man known to be the main architect of the Holocaust, Heinrich Himmler who stated,

‘The gypsies roaming the country as vagrants, who make their living mainly from theft, fraud and begging continue to constitute a plague. It is difficult to accustom the gypsy people, to whom German customs, traditions and character are foreign, to an orderly life. Nonetheless, the authorities must not flag in their efforts […] to get the gypsy plague under control. I therefore instruct you to use all available legal means – the police force in particular – in the fight against this social evil.’[3]

Deportation of Sinti and Roma in Asperg. Photo by Bundesarchiv, R 165 Bild-244-42 from Wikimedia Commons Bundesarchiv, R 165 Bild-244-42 / CC-BY-SA 3.0

Seven decades late

2 August, 2020 marks 76 years after the Zigeunerlager (Gypsy Camp) at Auschwitz was liquidated by murdering 2,897 Roma and Sinti in gas chambers. On this day, we commemorate the 500,000 Sinti and Roma who were murdered during the Nazi regime.

Although the European Parliament declared five years ago to recognize 2 August as Romani Holocaust Memorial Day, far too little has been done by European societies to protect Romani lives from continued segregation and trauma, and facilitate their healing from the Holocaust.

The discourse of the MEPs quoted above perpetrates stereotypes that reinforce racial resentment. This racist messaging continues to influence political and social views,[4] even in those who otherwise hold values of equality important.[5]

The sentiment these two MEPs present, along with many other European political representatives, mirrors Europe’s unwillingness to come to terms with its past, and allow survivors to heal, let alone for inclusion in the societies which Roma already belong to.

It is especially important to condemn such statements on Romani Holocaust Day – as well as any other time of the year – and to refuse the implications such as the ones MEP Janet alludes to, falsely suggesting that French Roma wouldn’t be French or didn’t deserve the support of France. Being excluded from the nation, written off as those who don’t belong, is always a vicious threat to minorities.

Commemorating 2 August is one step in the process of collective healing, mourning, and expressing the trauma that echoes in Roma communities today. The fact that it took 71 years for a European acknowledgement is painful enough already; the increasing political and social hostility makes it more difficult, yet all the more important to commemorate this year.

Hurting and grieving for generations

The trauma of the Holocaust has immense impacts on Roma communities still today. Research into the intergenerational consequences of collective trauma has primarily focused on the Native American genocide and cultural suppression and the Jewish Holocaust, but can help explain what Romani communities go through today.

Tessa Evans-Campbell, Associate Professor at the University of Washington School of Social Work defines it as a ‘collective complex trauma inflicted on a group of people who share a specific group identity or affiliation – ethnicity, nationality, and religious affiliation’, which translates to symptoms at the individual level, as well as on family structures and community outcomes across generations.[6]

One study conducted with Native American communities in the upper Midwest of the United States presented evidence of how past trauma is related to current mental health conditions and individual perceptions. The research centred on historical losses, like the loss of culture and language, dissolving family and community ties, the bereavement of the sense of safety in their community, and mistreatment by government and society. The inquiry has identified the links between these experiences and individual conditions in the current generation, such as depression, anxiety, loss of concentration, isolation, loss of sleep, anger, shame, rage, and avoidance[7].

Scholarship on the generational impacts of the Jewish Holocaust identified survivor’s syndrome in children of survivors, displaying ‘denial, agitation, anxiety, depression, intrusive thoughts, nightmares, and psychic numbing’.[8] The symptoms might not take as direct a form, although descendants are more likely to have increased ‘depression, higher levels of anxiety, mistrust, guilt, self-criticism, aggression and difficulty handling anger’[9]. Another study found that children of Holocaust survivors are more likely to develop PTSD when experiencing current traumatic events.[10]

What it takes to overcome

Roma have experienced slavery, genocide, cultural suppression, exclusion, segregation, and other forms of oppression and violence throughout centuries, and incidents continue to this day. European societies have not developed the means that would allow Roma communities to form resilience, healing structures and to cope.

Michael Ungar, the director of The Resilience Research Centre at Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia Canada details that ‘resilience occurs when there is an opportunity structure (an environment that facilitates access to resources) and a willingness by those who control recourses to provide what individuals need in ways that are congruent with their culture’[11]

Dr. Ungar conducted a mixed-method study with adolescents who experience stressful environments in 11 countries. The research indicated seven key factors associated with resilient responses in adolescents:

- supportive relationships;

- opportunities to experience powerful self-determination;

- experiences of efficacy;

- experiences of social justice;

- access to material resources like food, education and housing;

- a sense of cohesion within one’s family community or school;

- cultural adherence.

Europe cannot claim that Roma had or currently have equal access to these factors. Not to mention equal access to legal, political, and social instruments to redress and heal, especially after the community’s two largest collective trauma, slavery and the Holocaust. The actual resilience of Roma communities’ stems from the efforts of Roma communities themselves and the support of their families, not from wider societal support.

Statue of a Sinti girl, Ehra oder Kind mit Ball by Otto Pankok. Photo by Wiegels from Wikimedia Commons Wiegels / CC BY

Whose trauma matters

After Roma slavery was abolished in 1856, compensation or restoration was never on any political agenda. On the contrary, the Romanian state provided compensation to former slave owners for their economic loss thus authorizing that the slave owner’s economic loss as more significant than the trauma of 500 years of slavery itself. Again, Roma did not have access to national or international legal systems in which their suffering could be claimed. Having had no alternative due to the absence of supportive social, political, and economic environments meant that many Roma went back to their former slave owners to work.

Following World War II, governments and societies did not recognize or acknowledge the genocide of Roma. This led to an absence of voice, leaving no opportunity to claim themselves as victims of Nazi crimes against humanity, legally, socially or culturally. It wasn’t until 17 March 1982 that the German Federal Chancellor recognized the national socialist crimes against the Sinti and Roma as genocide based on race[12], thus creating a legal opportunity to demand reparations, already two generations later.

Discussion between the Central Council of German Sinti and Roma with the then Federal Chancellor Helmut Schmidt (1982) Photo by Dokumentations- und Kulturzentrum Deutscher Sinti und Roma – Dokumentations- und Kulturzentrum Deutscher Sinti und Roma from Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain.

Roma have had to build their own collective pathways to healing and resilience through art, speeches, plays, movies, rituals, and other commensurations. The first Romani Congress in 1971 also unified the Roma identity through common cultural markers, as well as through the shared history of social injustice and trauma during the Holocaust.[13]

The European racialization of the Roma community has deemed the group’s trauma less significant, or even inexistent. As Maurice Steven writes:[14], ‘racialization, sexualization, and the tyranny shape what trauma can be, which subjects its signification hails, and which institutional practices it underwrites because they are understood as adequate to its amelioration’.

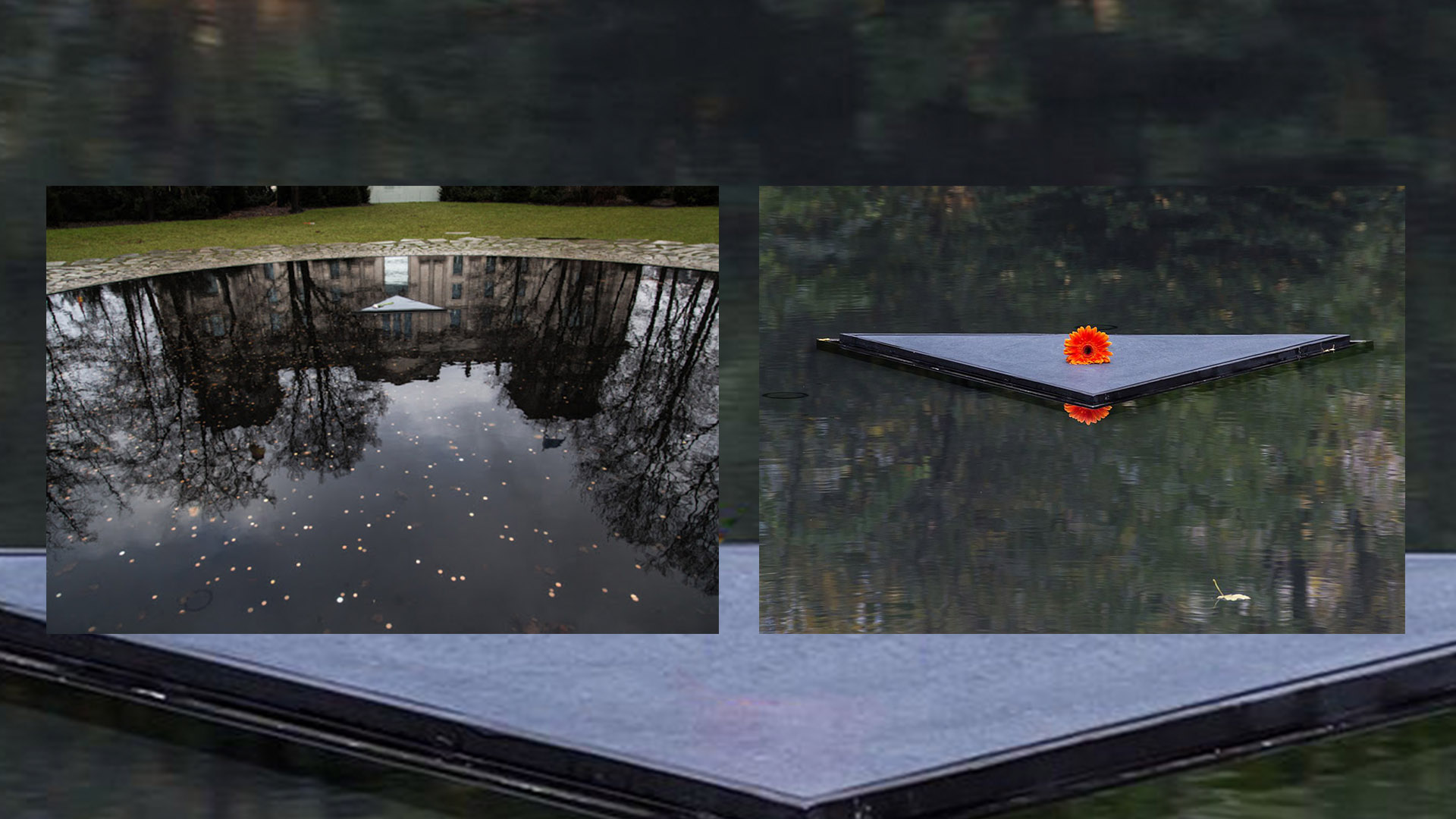

A Monument to the Porajmos: Sinti and Roma Holocaust Victims Remembered in Berlin Left: Photo by Dario-Jacopo Lagana from Flickr Right: Photo by Dietmar Rabich from Wikimedia Commons.

Deep wounds

Europe’s collective disregard for Roma trauma continues to this day. It is difficult to take the few existing efforts as genuine when MEPs openly insist that the EU should not support Roma inclusion, depicting Roma as criminals, attributing more value to their non-Roma citizens, while implying that Roma aren’t part of their nation. When the Romani Holocaust Memorial in Budapest was vandalized with the statement, ‘eradicating gypsies = eradicating crime’, without any condemnation by the Hungarian government. When the notoriously racist Bulgarian Minster of Defense develops a government proposal for dealing with the ‘problem with non-socialized gypsy groups’. When during the COVID-19 pandemic countless political leaders publicly dehumanize Roma, conduct discriminatory quarantining, and encourange police violence. When according to the Fundamental Rights Agency, school segregation for Roma has increased by 50% in European Member States since 2011. When the Sinti and Roma Holocaust Memorial in Berlin is planned to be removed to give space to a proposed train line expansion. When, as the European Roma Rights Center has documented, Roma have experienced ethic-based murders, demolitions of neighborhoods, and countless cases of mob violence.

A 2014 performance by Delaine Le Bas reflect on mob violence and police indifference.

Roma communities never got a break

How can a relentlessly persecuted community heal without the clear condemnation of the violence they endure, while also being barred by political leaders?

Roma communities simply never got a break. They have endured slavery and various decrees threatening their physical existence until 1856, followed by oppression, exclusion, and attacks following their formal emancipation as the public sentiment was building up for the next horrific crime, the Holocaust. In the aftermath, their losses and suffering were denied, coupled with the oppression of their culture, economic and educational suppression, attempts at forced assimilation, and social exclusion.

There has not yet been a time that would allow for recovery. The deficiency of political action indicates that facilitating Roma healing in not in the interest of European societies. The permanent attacks have not only fundamentally influenced the Roma community, they have also normalized the traumatization of Roma.

Europe must stop the exclusion

The first step is to end the perpetual trauma by responding to acts of violence and prejudice with unity and intensity. Leaders must start by condemning the hateful and dehumanizing speech of its own MEPs and national public representatives.

Second, European societies must construct safe and supportive environments that facilitate healing and resilience-building among Roma. Reconciliation requires equity in employment, education, and housing in a just society, where members of the Roma can determine their own lives without having to face discrimination or structural racism. In a fair society Roma can experience their cultural interconnection, and also feel the belonging and cohesion with their culture and within European societies.

Simply put, European societies must ensure that Roma are equally subject to the fundamental values of respect for human dignity and human rights, freedom, democracy, equality and the rule of law. Without ending the violence inflicted on them, or supportive social and political environments, a day of commemoration and some pockets of funding are not enough. Until these are provided, European and human rights values are denied from the twelve million Roma of the continent.

![]()

[1] Recording of European Parliament 09 July 2020 Plenary Session retrieved through the European Parliament Multimedia Center: https://multimedia.europarl.europa.eu/en/plenary-session_20200709-0900-PLENARY_vd?fbclid=IwAR1FmE_JNWldGW2icHpfW2vWDeg8c9HYvSTXpAQmIDB7RKOKFkGLc6I8G3Y

[2] Recording of European Parliament 09 July 2020 Plenary Session retrieved through the European Parliament Multimedia Center: https://multimedia.europarl.europa.eu/en/plenary-session_20200709-0900-PLENARY_vd?fbclid=IwAR1FmE_JNWldGW2icHpfW2vWDeg8c9HYvSTXpAQmIDB7RKOKFkGLc6I8G3Y

[3] Brückner, Dieter; Focke, Harald (2015): Das waren Zeiten 4: Neueste Zeit. New Issue Hesse. Bamberg: Buchner. [ISCED 2].

[4] Wetts, Rachel, and Robb Willer. ‘Who Is Called by the Dog Whistle? Experimental Evidence That Racial Resentment and Political Ideology Condition Responses to Racially Encoded Messages.’ Socius 5, 2019: 2378023119866268.

[5]Ziv, Talee, and Mahzarin R. Banaji. ‘Representations of social groups in the early years of life.’ The SAGE handbook of social cognition SAGE 2012: 372-389.

[6] Evans-Campbell, T. (2008). Historical trauma in American Indian/Native Alaska communities: A multilevel framework for exploring impacts on individuals, families, and communities. Journal of interpersonal violence, 23(3), 316-338.

[7] Whitbeck, L. B., Adams, G. W., Hoyt, D. R., & Chen, X., Conceptualizing and measuring historical trauma among American Indian people. American journal of community psychology 2004, 33(3-4), 119-130.

[8] Barocas, H., & Barocas, C., ‘Separation and individuation conflict in children of

Holocaust survivors’ Journal of Contemporary Psychology 1980, 38, 417-452.

[9] Felsen, I. ‘Transgenerational transmission of effects of the Holocaust’ In Y. Danieli

(Ed.), International handbook of multigenerational legacies of trauma (pp. 43-68). New

York: Plenum 1998.

[10] Solomon, Z., Kother, M., & Mikulincer, M., ‘Combat-related PTSD among second generation Holocaust survivors: Preliminary findings’ American Journal of Psychiatry 1988., 145, 865-868..

[11] Ungar, Michael. ‘Resilience, trauma, context, and culture.’ Trauma, violence, & abuse 14.3 (2013): 255-266.

[12] Mirga-Kruszelnicka, Anna, Esteban Acuña, and Piotr Trojański. ‘Education for Remembrance of the Roma Genocide.’ Cracow: Wydawnictwo LIBRON (2015).

[13] Hancock, I. (1991). The East European Roots of Romani Nationalism. Nationalities Papers, 19(3), 251-268.

[14] Maurice Steven, ‘From the Past Imperfect: Towards a Critical Trauma Theory’, The Semiannual Newsletter of the Robert Penn Warren Center for the Humanities Vol. 17., No. 2. Spring 2009.