‘Something very lightweight arrived for you today, not like yesterday. Yesterday it felt like I was carrying stones. I hardly made it to your door!’ The package was indeed super light – good for the delivery guy, bad for us. He thought he was jokingly complaining, but both did contain stones. Or, at least, they should have – we had put them there ourselves when we were taking down our Reconstruction of Memory exhibition at DOX Centre for Contemporary Art in Prague to send the installed works back home. When we unpacked the second, disturbingly lightweight package, only five stones were trapped in endless layers of bubble wrap. They could all fit in a single palm.

And these were not arbitrary stones. They were pebbles from Crimean beaches, which we had sought via social media and meticulously collected for the installation The Beach. The work comprised of pebbles that tourists had taken home from Crimean shores. Almost anyone who had ever visited Crimea had a similar pebble somewhere at home – a souvenir from a vacation, an actual part of a place as its physical momento, a piece of their own personal Crimea. After the annexation, this fragmented Crimea, hidden all over Ukraine in cabinets, drawers and sometimes aquariums, became the only one we had left. Together with Julia Po, we decided to reassemble the pebbles that we received from friends and total strangers, one by one, into a real beach – 28 kilos of memories of sun, sea and rest.

The Beach, Lia Dostlieva and Julia Po, installation view, IZOLYATSIA, Kyiv, 2016 (photo by Julia Po).

This newly made ‘Crimea’ had travelled quite a bit – we had shown the Reconstruction of Memory exhibition in Kyiv, Warsaw, Poznań and Prague. And, every time we had laid out those pebbles one by one and picked them back up one by one after the exhibition was over. When installing the piece at DOX, we felt that we could recognize some individual pebbles by touch. After the exhibition had closed, we packed up the pebbles as usual and handed them over to the delivery service. The first box arrived safely. The second, a slightly larger one, was damaged en route. So, what had happened to its contents? Apparently, after the destroyed box started haemorrhaging plain stones, they went straight into the trash. The last few stones that remained were brought to us by that cheerful delivery guy.

The transport company sent us several forms which we had to fill in to file a complaint. Among others, there was the obvious question: what is the estimated value of your cargo?

Indeed, what was it?

Our cargo was immensely dear to those who understood what it was and, at the same time, totally worthless to those who saw it only as a pile of stones.

This story is a good example of the non-obviousness and opaqueness of the symbolic value of certain objects. The space of remembrance that we tried to create in our exhibition when taken out of its original context and stripped of textual description became a mere pile of stones, mere trash.

Empathy requires understanding. Working with traumatic memories requires a lot of explaining. But who should explain trauma and how?

Back then, we chose not to file any formal complaint.

Acknowledging trauma

We had lived in Donetsk for almost all of our lives, but the annexation of Crimea and the military conflict in Donbas that followed happened when we were both abroad. We learned that our hometown had been occupied on the news. The sensation of absence and loss of our home was highly disturbing yet was meaningful on an artistic level: it established a personal link with the context of war and occupation and simultaneously created a certain distance – both critical and physical – which is very opportune for an artist. We began working with traumatic experiences, using our own as a starting point.

Certain questions are always troubling when working with trauma: what is my own access point to this theme?; what can legitimize my right to speak out?; am I unwittingly appropriating the agency of the group I am trying to speak about? Markings on the ‘superiority-critical look-empathy-autotherapy’ scale are not always easy to read, especially when it comes to personal artistic practice.

Reconstruction of Memory, exhibition view at IZOLYATSIA, Kyiv, 2016 (photo by Dima Sergeev).

Reconstruction of Memory, our first large-scale project about traumatic experiences, gathered together artists who were either expelled from their homes by Russian occupation or, like us, left without a chance of returning home. It was an attempt not even to find an answer but rather to pose certain questions: what can those who were forcibly displaced and lost everything do with their familial memory?; and is there a way to restore the lost items that once enabled storytelling about their own past – family albums, heirlooms, memorabilia – by speaking about their loss, at the very least? One of the works in this exhibition was the now lost Crimean beach.

We began working on the project in the summer of 2015. Then, it seemed that the war could end at any moment and everything would go back to normal. Feelings of dismay and being lost caused by the very fact that war was suddenly not just some abstract fact from school history books but part of our personal story seemed to be a dominant mind-set during that period. Some of the artists we invited eventually declined – the events were too recent and traumatic to find enough distance from them to create artwork.

Sergei Zakharov, Terra-icons, installation view, IZOLYATSIA, Kyiv, 2016 (photo by Dima Sergeev).

The first edition of Reconstruction of Memory took place in the newly established IZOLYATSIA Foundation exhibition space, Kyiv, which had its own troubled history of occupation and a narrow escape. The foundation’s premises in Donetsk, a former isolation materials plant, was occupied by pro-Russian militants in summer 2014. The majority of items in the foundation’s collection were site-specific objects that could not be evacuated so were mostly destroyed by the militants. The foundation team escaped to Kyiv. Their former buildings in Donetsk are still being used today as a prison and torture chambers, where an unidentified number of prisoners are being held in inhumane conditions.

Russian occupation has turned the centre of contemporary art into a concentration camp. Sometimes reality exceeds any artistic gesture.

Understanding trauma

In his article Beyond the suffering subject: Towards an anthropology of the good, Joel Robbins notes that meticulous attention to the savage Other – a significant subject of anthropological studies undertaken in the ’80s – could not fulfil the needs of both society and the humanities, leading to the suffering human figure’s rise as a new subject of anthropology and humanistic studies in general.[1] As Didier Fassin and Richard Rechtman rightfully note in their book The Empire of Trauma, in the last two decades, ‘trauma had become an essential human value, a mark of the humanity of those who suffered it and of those who cared for them’.[2] They continue: ‘the human being suffering from trauma … became the very embodiment of our common humanity’.[3] An understanding of trauma and suffering as universal human experiences capable of overcoming linguistic and cultural barriers has replaced the patronizing gaze of a researcher bearing ‘objective’ knowledge. The universality of traumatic experience enables bidirectional empathy.

Appreciating traumatic experience as an event that can create a unifying discursive field rather than separating those with or without said personal experience was crucial for Reconstruction of Memory. Without creating a space for common dialogue, it is impossible to embed the difficult memory of a separate social group into the master narrative.

In bringing the issue of Internally Displaced Persons’ familial memory lost due to war and occupation into public discussion, we face the social unpreparedness of seeing IDPs as something other than silent recipients of charitable aid. Paradoxically, the loss of homes leads to a huge social group of people being classified as those without agency and, therefore, unable to form personal statements and be rightful actors in social discussion.

Reconstruction of Memory, exhibition view at DOX Centre for Contemporary Art, Prague, 2017 (photo courtesy of DOX Centre).

‘The sole clear feeling that I get from viewing the Reconstruction of Memory is endless pity for the authors. If there was a bank account number for donations under every project, I would certainly send them some money – over the last few years, this has been the only act I have seen that helps at least partly to cope with the guilt I feel for having avoided their tragic fate’, wrote one Ukrainian art critic about the exhibition at IZOLYATSIA. Our exhibition had produced such a powerful emotional response that the author felt the urge to ‘pay a ransom’ to escape the issues they suddenly faced, using unsolicited charity to shield themselves from reflecting on the experiences of a certain social group. This response is a good example of how belonging to a vulnerable group can be instrumentalized to reject the group’s legitimacy. Furthermore, it proves how shared traumatic experience might be used as an instrument for denying agency and denigrating ‘subject’ into ‘object’.

During the first years after the beginning of the war, IDPs were only spoken of in the context of aid. And that means aid in satisfying the most basic needs – finding a home, a job, clothes, kindergarten places for children. But what could be done about the memory of this social group? As Oksana Dovgopolova notes in her essay ‘Ruptures’ of collective memory: The problem of exposing and curing, the memory of displaced people creates a rupture in the fabric of Ukraine’s past, which demands previously unknown tools for it to be fixed. The ‘seam’, as Dovgopolova notes, can be applied in different ways – either by cutting out a piece of the past and sewing ‘over the top’ or by finding a mechanism to embed new fragments into an established commemorative fabric. Until a language is found to speak about this rupture, it will not be felt as an acute social issue, entering the space of the ‘archive of remembering’, a source for the creation of dangerous mythology.[4]

The following two first-hand accounts describe artistic means of dealing with such rupture.

Lia Dostlieva’s 298

On 17 July 2017, I performed a commemorative action in honour of the 298 victims who died in the MH 17 crash not far from my home city exactly three years before. Together with friends, acquaintances and strangers, 298 small dolls were created, one for each person who was killed in the crash. It took us eight hours; I thought it would take much longer.

Boeing MH 17 was shot down on the same day I turned thirty. This coincidence strengthened my sense of guilt due to my detachment from the war in my city. I was living abroad at the time and went online to check my birthday greetings. Instead, I read the breaking news. The collective creation of 298 figures emerged from my desire to make a commemorative gesture that could create a shared space of remembrance able to accommodate both my guilt and willingness to remember.

298, Lia Dostlieva, performance documentation, 2017 (photo from the author’s archive).

I performed in a public space in Poznań. The event, which was documented live on Facebook, quickly made it into the Ukrainian press. The news snippets were all similar: ‘a displaced Ukrainian from Donetsk making red dolls near a fountain in Poznań, Poland’; ‘a displaced woman from Donetsk made 298 dolls to commemorate MH17 victims’; ‘Ukrainian woman organized a memorial event’. Only a few articles used the word ‘artist’ after other objectifying keywords had already been depleted.[5]

Despite my personal sense of detachment from the war in the Donetsk region, the journalists were absolutely sure that the most important thing to communicate was my nationality, my status as a ‘displaced person’ – albeit not technically true, as I left Donetsk shortly before the war started – and my belonging to a certain social group but not a professional one.

Why? Each of these social constructs – ‘displaced person’ and ‘artist’ – carries an established meaning that does not require additional explanation. A ‘displaced person’ is a member of a socially vulnerable group, a person in need, homeless and problematic by definition. ‘Artist’ suggests a person with status supported by institutional authority and the ability to make statements using professional tools. Had the commentators written ‘an artist from Donetsk made 298 dolls to commemorate MH17’, the item would have immediately lost its drama.

298, Lia Dostlieva, performance documentation, 2017 (photo from the author’s archive).

Andrii Dostliev’s Occupation

Six years ago, in spring 2014, Russian terrorists, calling themselves the Donetsk People’s Republic, occupied my hometown in eastern Ukraine. I was lucky to already be living abroad when it all started. Many of my friends were not so lucky and, that spring and summer, moved out of Donetsk one by one to Kyiv, Lviv, Kraków and even London. ‘It’s only for a couple of months’, some of them would say, ‘we’ll return as soon as it all ends’. We talked a lot back then about what we had lost, though we preferred to think of it as ‘temporarily inaccessible’. Family photo albums fell into that category.

I never cared much about my own family photo archives back then. Sure, I used to go through the photos sometimes when I was younger. I’d ask my family members about the stories behind some of the images, but I never really thought of them as something important. They were just permanently there. And then they suddenly became ‘temporarily inaccessible’. They were taken from me and I suddenly felt their loss. The idea of reconstructing my family photos came to me for the first time in autumn 2014, but I was not particularly eager to pursue it, because I would see them again soon after all. It would have been a waste of time to start the work and then a month or two into it see Donetsk liberated and everything go back to normal.

Andrii Dostliev, Untitled #1 from Occupation series, 2015.

‘This woman in the photo from the flea market in Riga looks remarkably like my grandmother in her 30s. She had a similar photo – same pose, same three-quarter view, similar clothes. She must have liked it – she even had an enlarged hand-coloured copy made. The aubergine, sleeveless dress she was wearing in that photo lasted long enough for me to remember it.’

But, five years ago, in spring 2015, I finally started working on my photographic series Occupation, for which I became well known. By that time, I had already given up all hope of war coming to an end soon. My hometown, my flat there and everything in it were not ‘temporarily inaccessible’. They were lost for the long-term if not forever. I started writing down descriptions of photos from our family archive that I could still bring to mind with the plan of turning them into collages later on.

That spring was a rather intense time for me as well as many other Ukrainians abroad, who were checking the news websites compulsively and looking for ways to help people back home. I was living in Riga. It was my Erasmus+ term and I had made a very poor choice of receiving institution: ‘oh look, there’s a Latvian university on the list, I want to go to Latvia, that would be cool, right?’ had brought me to what turned out to be a private academy for Russian-speaking Latvians. At my first meeting with my new ‘classmates’ without even asking for my name, they asked me where I was from. And, after I answered, they immediately informed me that ‘you should realise that we will never give Donetsk back to Ukrainians.’ Thus ended our first and last conversation.

And so, I was alone and anxious without much to do for the next six months. I would go to the flea markets and garage sales looking for old photographs that would either remind me of the photographs from my family albums or at least depict a scene that I could later use. Then I would sit at home with those photos and my notes, pencils, acrylic paints, sketchbooks, scissors and glue, trying to rearrange the pieces into a familiar picture. Only formal visual resemblance mattered – it was never about the finesse of the final image nor its credibility. The pictures looked intentionally absurd, because the whole idea of being able to remake something dear to you from bits and pieces was absurd. Or, at least, it seemed to be so back then.

Andrii Dostliev, Untitled #21 from Occupation series, 2015.

‘My first photo. I’m ten months old or so, I’m in my crib behind a safety net. Everything is blurred and barely visible, just like my memories.’

I came up with the title Occupation for the series and was immensely proud of it. It was about the occupation of not only Donetsk but also my family history. It described perfectly the method I was using – appropriating or ‘occupying’ other people’s family photographs and, therefore, the memories that ended up at flea markets. In my descriptions of the photos, I was also repeatedly and unintentionally at first referring to other cases of occupation – there were photos from Abkhazia occupied by Russia in the 1990s, photos from Crimea occupied by Russia in 2014, my childhood photos from Chișinău that were taken at the same time Russia occupied Transnistria. And, finally, the flea markets photos that I was using for my collages also originated from the era of Latvia’s Soviet occupation. The notion of occupation was diffuse throughout the project.

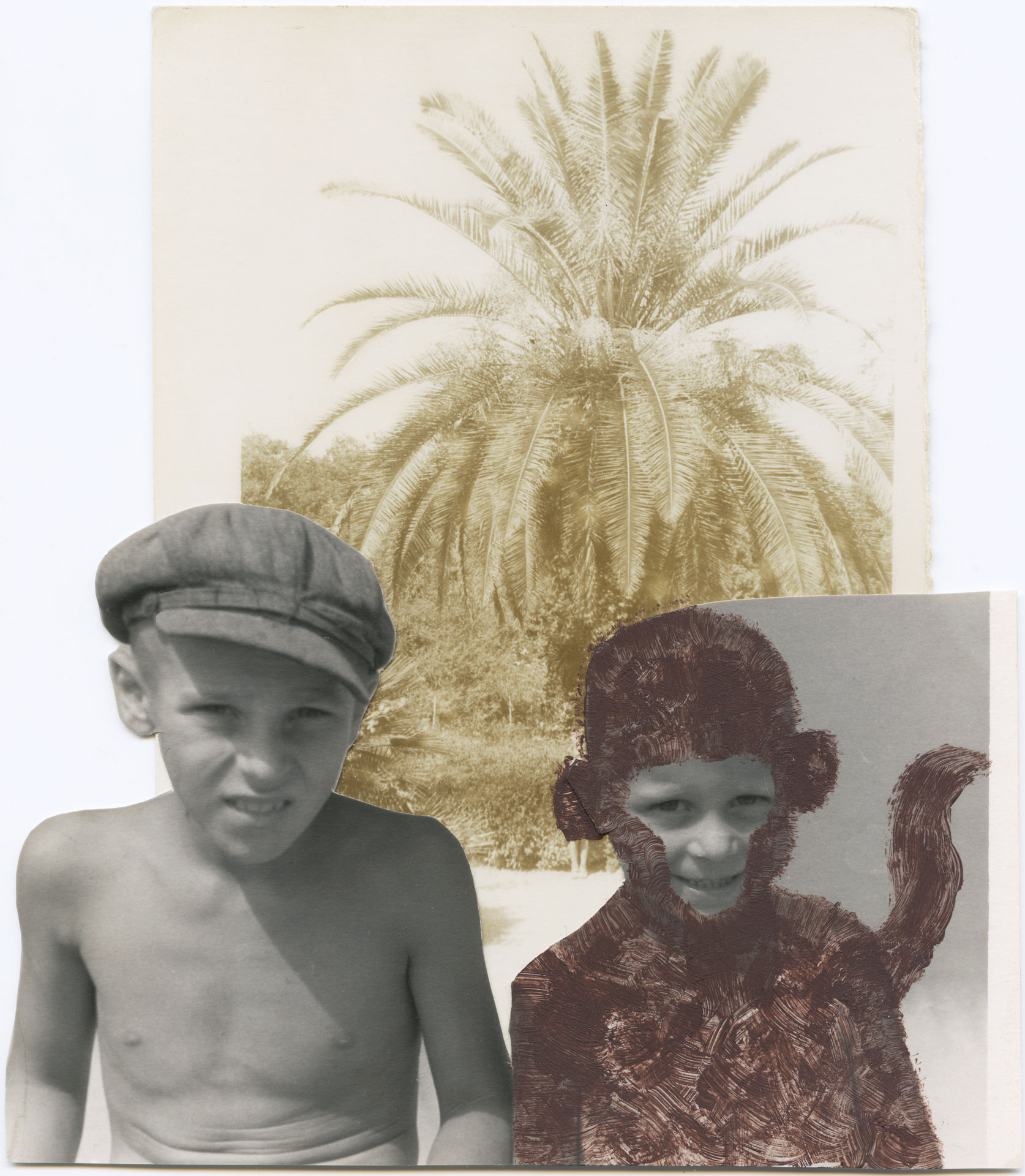

Andrii Dostliev, Untitled #26 from Occupation series, 2015.

‘And here I’m six or maybe even seven. It’s a common summer holiday photo on a beach against a prop palm tree with a toy monkey. It was taken in Crimea some twenty-five years before its Russian occupation.’

By July 2015, I had accumulated some thirty collages that were paired with descriptions of the original photos from my archive. I had to stop at some point because I was running out of ideas, time and emotional resources. Not all of the descriptions I had started with found a visual pair and some of the collages I produced were after some consideration discarded from the series. It started with a photo that I hand coloured of an unknown Latvian girl who looked remarkably like my grandmother in her thirties and eventually spun off into a tale of three generations of my family in pictures. Unlike the real photos, the collages were and still are always there for me.

In spring 2020, self-isolated and having depleted my procrastination resources, I began working on a new project based on archival photographs that used to belong to Ukrainian forced workers, collectively called Ostarbeiter, in Nazi Germany. I knew that my grandmother was one of those young girls who were taken to Germany to work – ‘у баура’ (at the Bauer or farmer’s), as another Ukrainian girl would describe it in her letter to a friend of a similar fate, carelessly mutilating and at the same time embracing the German word into our native language. I knew my grandmother had a single photo that she brought back from Germany as a bitter reminder of those times. I had to know – after all, it was one of the pictures that I had reconstructed earlier in the Occupation series.

Andrii Dostliev, Untitled #2 from Occupation series, 2015.

‘This picture was particularly important to my grandmother. It was taken shortly after the Nazi forced labour camp in Sudetenland where she was being held was liberated by the Soviet army. She and her friend and two Soviet soldiers made a group studio portrait to celebrate the first moments of their freedom.’

I realized that my grandmother’s photo could maybe be of some use for my new project and tried to recall it from memory. And quite naturally failed. All I could recall was the image I made myself five years ago to replace the photo she had brought home from Teplitz-Schönau in 1945. It had done its replacement job perfectly. And it felt natural now despite all its crudeness and, speaking quite frankly, monstrosity (and, yes, this is a reference to Frankenstein’s monster). It was still an irregularly shaped image with two seated Latvian girls and two slightly undersized Soviet soldiers and yet I got used to thinking of it as if it actually were her photo.

And it made me suddenly realise that the same had happened with the other photos as well. They had been there long enough to effectively replace the originals in my mind. The discomfort caused by the crudeness of the collages had washed away, leaving the warmth of memories attached to the photos. The face of an unknown Latvian girl whose portrait and accompanying text began the series had actually replaced my grandmother’s face in my dreams.

Once again, the key point of both the Occupation series was the absolute inability of a human being to replace lost memorabilia with their reconstructions. I was absolutely convinced in that. But it now appears that I might have been wrong.

Nevertheless, no matter how attached I had become to that collage of mine, it was still of absolutely no use for the Ostarbeiter project. I had to pull some strings before eventually being able to obtain a few scanned pictures from my family albums – the real ones this time. I then had copies of around ten per cent of all my family’s photos. The choice was quite random, but there was still a good chance that the photo I was looking for was there.

As I went through them, I encountered some images that I had reconstructed earlier and could finally compare the two. The ones I easily remembered five years ago turned out to be pretty similar, as expected. Others that I had reconstructed based on a certain situation rather than a particular image turned out to be uncannily similar too: for example, the generic photo from Sukhumi was not that difficult to recreate, due to its ubiquitousness in Soviet photo albums.

Left: Andrii Dostliev, Untitled #2 from Occupation series, 2015.

Right: image from Andrii Dostliev’s family archive, photographer unknown, 1969.

Not all of the photographs I had remembered were among those scans that I managed to obtain. Indeed, most were not. I did not find the photograph of my Grandma to match the coloured portrait of a girl that had replaced her in my memories. I found another one instead, taken some fifteen years later probably, where she appears to be wearing the same clothes that I was trying to reproduce so meticulously. I recognize her in this photo and, at the same time, I’m not sure that I really do. I mean, I definitely know it’s her photo, but it would be so much easier for me to really recognise her if she looked just a little bit more like the Latvian girl that I had replaced her with. The coin has flipped and Barthes’ distressing ‘almost the way she was’[6] now relates to the original photograph.

Image from Andrii Dostliev’s family archive, photographer and date unknown.

And no, I didn’t find the picture that I was looking for. I don’t expect I ever will now.

When I first shared my collages, someone mentioned Holocaust survivors who would sometimes put photos of total strangers on their walls to create an illusion of continuity, of their family history, after the loss of their own archive. It’s an anecdote that I have never encountered in any other form since. Back then it sounded so tragic and desperate. And, although it still sounds just as traumatic today, at least I now understand that it may have actually given them some comfort.

[1] J. Robbins, ‘Beyond the suffering subject: Towards an anthropology of the good’, Journal of the Royal Anthropological, Vol. 19, No. 3, Sept 2013, p. 453.

[2] D. Fassin and R. Rechtman, The Empire of Trauma, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2009, p. 140.

[3] ibid., p.23.

[4] Оксана Довгополова (Oksana DOVHOPOLOVA). «Розриви» колективної пам’яті: проблематика виявлення та лікування. Україна Модерна. 2019, No. 26, pp. 141-161, http://dx.doi.org/10.30970/uam.2019.26.1105

[5] Ukrainska pravda corrected the title of their article after my outraged Facebook post.

[6] See: R. Barthes, Camera Lucida, New York, Hill and Wang, 1981, p.66.